Evacuation 4

What might be some problems about children being

sent from cities to the countryside?

• Children had never been to the countryside

before

• Children had never seen real livestock (cows,

pigs, hens etc) before

• Children might have had indoor toilets at

home, but in the country, the facilities were

often

at the end of the garden and were basically a

hole in the ground …

• Children might not know the local dialect and

might not understand what the local people

were saying

• Children might get cruel people to stay

with

• Children might get people who expected them

to work hard

And many more.

Also, many children were sent abroad, not just

to the countryside.

For some children it was a brilliant

experience, but for some, it was a bad time.

Some were, for the first time, living a good

life with lots of good fresh food; some were

expected to work all day (say on a farm)

although each local person was paid to take the

children.

Some children were abused either physically or

sexually; there was nothing to be done.

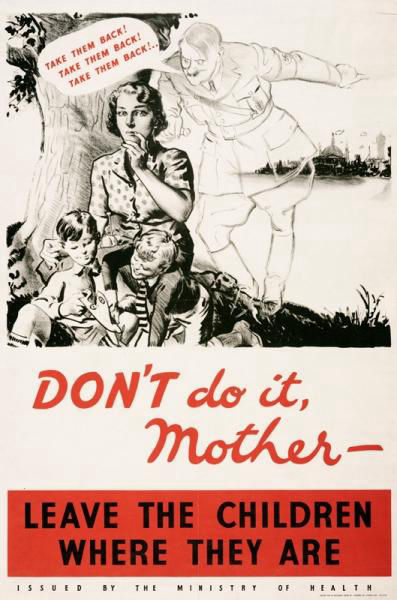

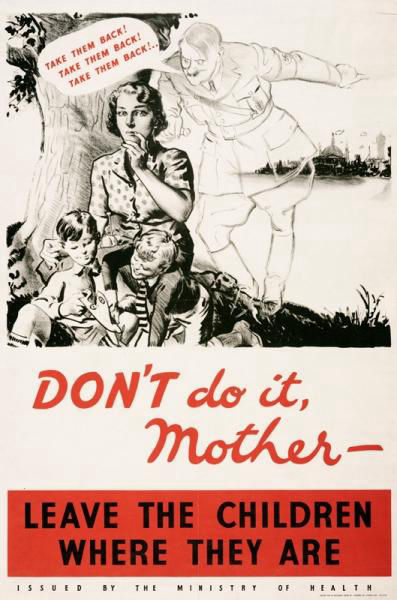

Yet, evacuation was not compulsory and some

parents were understandably reluctant to take

part, despite propaganda posters which

encouraged co-operation. For those parents who

did co-operate it would be a nervous wait of

several days to find out where their children

had gone with notification coming via a postcard

through the mail.

It was one thing to remove children from

at-risk areas, but it was another to find

somewhere for them to go. Various options were

discussed, with civilians generally preferring

the option of camps to be set up and supervised

by teachers, but government ministers instead

decided to use private billets. It became

compulsory for homes to host assigned evacuees,

with host families being paid 10 shillings and

sixpence (53p; equivalent to £26 today) for the

first

unaccompanied child, and 8 shillings and

sixpence for any subsequent children.

Places were assessed in terms of accommodation

available rather than suitability or the hosts’

inclination for raising children. This could

lead to resentment of those who would be forced

to care for children against their will,

compounded with that many children did not want

to be there in the first place and tried to run

away. This problem was particularly prevalent in

the lower-class families, as wealthier families

often had relatives or school friends in the

country to take in their children, rather than

relying on strangers.

Obviously, parents and children often missed

each other. In the ‘Phoney War’ that followed

the start of the Second World War, Hitler was

not ready for a full-scale attack on Britain and

France. This meant uneventful months passed,

giving a false sense of safety, so many children

began to come back. Despite warnings by the

Minister of Health, nearly half of all evacuees

had returned to their homes by Christmas. But,

when France fell in June 1940, Britain became

the next target and the Blitzkrieg began.

What was ‘the Phoney War’?

This was the time between war being declared

(September 3rd 1939) and the first attacks by

Germany on the British mainland (April

1940).

The government had to keep reminding parents to keep their children away and remind them what they were fighting for - even on the Home Front.

Here's a strong poster used to try to persuade

parents to keep their children away.

And then the war started in England fully. Cities such as London, Coventry, Birmingham,

Swansea, Plymouth and Sheffield were pounded mercilessly and evacuation became a policy grounded in reality. The south coast of England was also quickly changed from a Reception area to an Evacuation area due to the threat of invasion and so 200,000 children were evacuated (or re-evacuated) to safer locations. This ‘trickle’ evacuation continued until the end of 1941, but even after the Blitz ended, danger remained.

We do not look at the Blitzes in much detail

because that’s a whole subject in itself. Here,

though, is an iconic picture:

And lots more HERE.

Air attacks continued sporadically, then in

1944 an entirely new threat arrived in the form

of Hitler’s V-1 flying bombs and V-2 ballistic

missiles. This began Operation Rivulet, the

final major evacuation of the war. Running

between July and September 1944 more than a million people moved out of danger

zones.

To try and ease the blow of being separated

from their parents, a special song was written

for children in 1939 by Gaby Rogers and Harry

Philips, entitled ‘Goodnight Children

Everywhere’ and broadcast every night by the

BBC:

Goodnight Children Everywhere

Sleepy little eyes in a sleepy little head,

Sleepy time is drawing near.

In a little while you’ll be tucked up in your

bed,

Here’s a song for baby dear.

Goodnight children everywhere,

Your mummy thinks of you tonight.

Lay your head upon your pillow,

Don’t be a kid or a weeping willow.

Close your eyes and say a prayer,

And surely you can find a kiss to spare.

Though you are far away, she’s with you night

and day,

Goodnight children everywhere

Soon the moon will rise, and caress you with

its beams,

While the shadows softly creep.

With a happy smile you will be wrapped up in

your dreams,

Baby will be fast asleep. Goodnight children

everywhere.

Not only are those the words but

HERE'S

the actual song!

You also have to remember that not all children

were evacuated in the first place. Evacuation

was a voluntary process and, while blackouts,

gas masks and other wartime changes were

accepted, many parents refused to part with

their children during the war. Parents’ concerns

were not helped by the fact that the government

could often not even tell them where their

children would be going, and so only about 47

per cent of children were actually evacuated in

the initial wave. Just under half of children in

the danger areas.

It didn’t help at all that the Phoney War

happened, when there was no action against the

British mainland by Germany. Parents who had

sent their children away wondered why they had

gone through all the hassle and upset, the

loneliness and even the long journeys to visit

the children once they had arrived. Many brought

their children back home.

And then, as mentioned above, the war proper

started and suddenly parents wanted to get the

children out of the danger areas. And of course

they were allowed to go, the government

helped.

This evacuation seems generally to give the impression that it was not very nice, generally, but in fact, although there were bad times for some children, for most of the evacuated children (and mothers etc) these were fantastic times.

For some children, it was the first time they had seen more grass than a tiny front or back garden (if they were lucky); many reported being amazed at the size of a cow. They’d only seen farmyard toys before and thought that a cow was a pretty small animal. For many of the children, apples came from a shop - in the countryside they were stunned to see many apples having on trees! The sights, smells and sounds were totally new to many of the children - if they came from cities then they were perfectly used to buses coming along every few minutes, but in the country, one bus a week was often the case. They were used to houses being connected to each other (terraced houses) but in the country, houses, although really tiny, often, were set in their own gardens and ‘next door’ night be a hundred metres away.

When the war finished, coming home was often

joyous, a reunion with families and their own

cities, the places the played and the schools

they had disliked but which added to the sense

of ‘home’.

Unfortunately, many city children returned to

different areas.

Why might that be?

Because their homes and areas had been

destroyed by the bombing of the Germans.

Not only that but there were many cases where

the children arrived back home, four or even

five years older, with changed minds and changed

attitudes. The parents often expected that the

children would be more or less the same as they

had when they were evacuated (except for being

older of course) but they didn’t expect the

changes in the way their own children thought

and acted.

As you know, your thoughts and minds change a

lot between being about 9 and about 14, and this

led to conflict between mothers and children;

not only that but slowly fathers came home too,

after being released from the forces.

Quite a lot of children, far from being happy

to be back home, found that they were very

unhappy - gone were the open fields, the cozy

farmhouses or the comfy cottages they had been

living in for the last few years. Gone was the

clean air and the more plentiful food - berries

from hedgerows, fallen apples and fruit,

actually seeing real-life animals.

Arriving back in a tiny house in a crowded

city, polluted, constantly noisy and often with

many bomb-sites just wasn’t what they expected.

Their friends had often been sent to other

evacuation areas, and they had made new friends

in the places to which they had been

evacuated.

But, without Operation Pied Piper, many more people would have been killed in the blitzes on cities in England - one bombed house might have a mother inside, and maybe a grandmother too, but not an extra 2 or 3 children.

More than two and a half million children were

evacuated, and many from the other evacuation

groups too. It wasn’t just that they had to

leave the danger areas - after all, most people

travelled on some sort of excursions (one-day

trips) or even holidays and that wasn’t a

problem.

So what was the other type of problem?

Emotional problems.

When children went away, and came back again,

and the times in between, it was emotional. It

could be exhilarating or upsetting, an adventure

or something scary.

These emotions, especially the negative ones, were just as much ‘sacrifices’ as were men joining the forces or women working long hours in factories.