Hatred all around you

makes you believe it

Hatred all around you

makes you believe it

7.1 Legal discrimination

Key question: Did Nazi anti-Semitism change over time?

Base answer: yes, it became considerably stronger

Key dates:

First official boycott of

Jewish shops and professions 1 April 1933

Nuremberg Race Laws

introduced: 15 September 1935

A boycott of Jewish shops was organised

for April 1st 1933. Soldiers and members of the

Nazi party stood outside Jewish shops and tried

to persuade people not to use those shops on

those days.

However, it did not really succeed and many

Jewish shops were used as usual.

In addition, it was bad publicity for Germany

aboard as other countries could see that there

was anti-Semitic action.

Feelings of hopelessness were soon replaced by those of fear. To show sympathy for, or to protect Jews, was to risk one’s own freedom or one’s own life.

Der Stürmer was an anti-Semitic newspaper, pinned up all over Germany, spouting lies about the Jews. Propaganda against was no more obvious than this newspaper.

Radical Nazis wanted to take immediate action

against Jewish people and their businesses, but

even the party’s leadership was worried that it

could get out of hand - an uprising could easily

turn against any authority.

A one-day

national boycott was organised for 1 April 1933.

Jewish-owned shops, cafés and businesses were

picketed by the SA, who stood outside urging

people not to enter.

However, the boycott was not universally

accepted by the German people and it caused

a lot of bad publicity abroad.

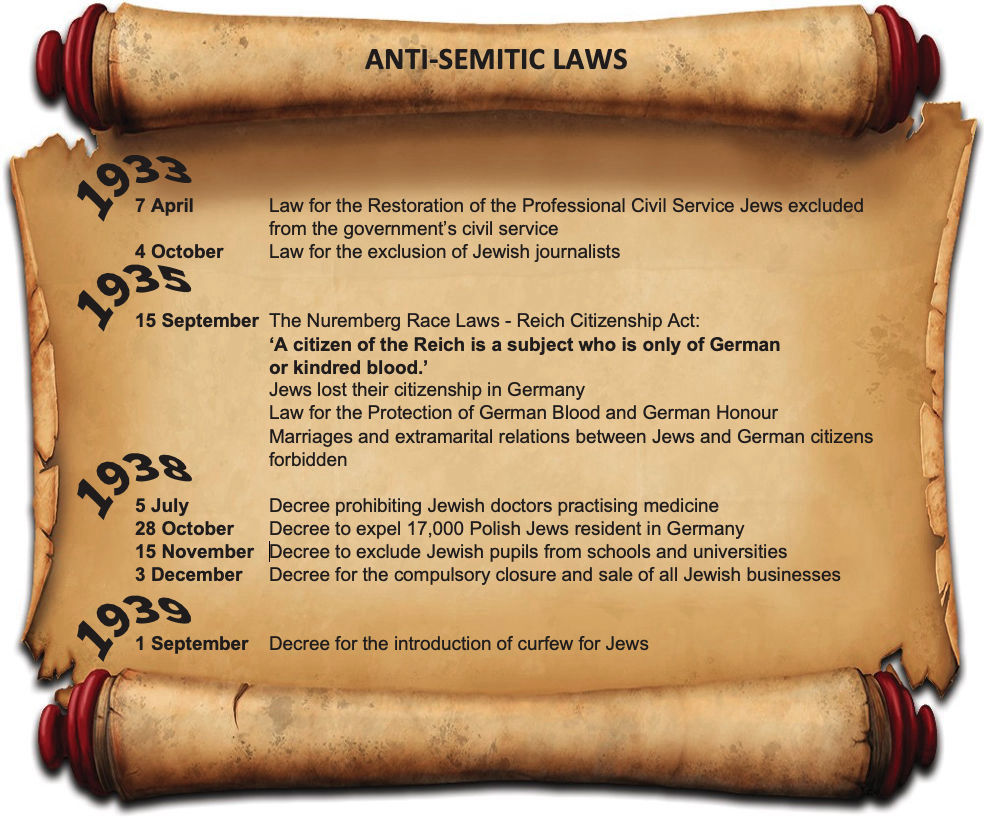

The Nazi leaders developed their anti-Semitism

in a more subtle way. Once the Nazi regime had

established the legal basis for its

dictatorship, it was legally possible to

initiate an anti- Jewish policy, most

significantly by the creation of the Nuremberg

Laws in September 1935. This clearly stood in

contrast to the extensive civil rights that Jews

had enjoyed in Weimar Germany. The

discrimination against Jewish people got worse

as an ongoing range of laws was introduced. In

this way all the rights of Jews were gradually

removed even before the onset of the war.

Here’s an illustration showing the Anti-Semitic

Laws and their effects.

2.1 Propaganda and indoctrination

Nazism also set out to change people’s attitudes, so that they hated the Jews. Goebbels himself was a committed anti-Semite and he used his skills as the Minister of Propaganda and Popular Enlightenment to indoctrinate the German people.

All aspects of culture associated with the Jews were censored. Even more forceful was the full range of propaganda methods used to advance the anti-Semitic message, such as: posters and signs, e.g. ‘Jews are not wanted here’ newspapers, e.g. Der Angriff; Der Sturmer, edited by the Gauleiter Julius Streicher, which was very anti-Semitic with a seedy range of articles devoted to pornography and violence cinema, e.g. The Eternal Jew; Jud Süss.

An aspect of anti-Semitic indoctrination was

the emphasis placed on influencing German youth.

The message was put across by the Hitler Youth,

but all schools also conformed to new revised

textbooks and teaching materials, e.g. tasks and

exam questions.

2.1 Terror and violence - Key dates

Night of the Long Knives (murder of opponents): June 30–July 2 1934

Kristallnacht (Crystal Night), anti-Jewish pogrom: 9–10 November 1938

Creation of the Reich Central Office for Jewish Emigration: 1939

In the early years of the regime, the SA, as the radical left wing of the Nazis, took advantage of their power at local level to use violence against Jews, e.g. damage to property, intimidation and physical attacks.

After the

Night of the Long Knives in June

1934

(an organised execution of anyone thought to be

against Hitler), anti-Semitic violence became

more sporadic for perhaps two reasons.

First, in 1936 there was a decline in the

anti-Semitic campaign because of the Berlin

Olympics and the need to avoid international

alienation (see next page). Secondly,

conservative forces still had a restraining

influence.

The events of 1938 were on a different scale. The union with Austria in March 1938 resulted, in the following month, in thousands of attacks on the 200,000 Jews of Vienna.

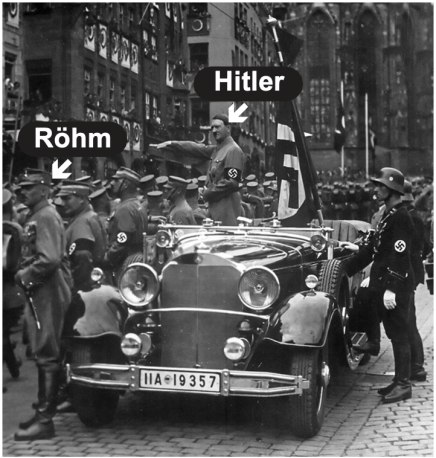

In the Night of the Long Knives,

Ernst Röhm, Hitler’s best friend for

years, and 400 other Brown Shirts

and the leaders of the Brown Shirts

were murdered to consolidate

Hitler’s grip on power.

Anti-Semitism in Germany was becoming much worse and in 1938, on 9–10 November there was a ‘sudden’ violent pogrom against the Jews, which became known as the ‘Night of Crystal Glass’ (Kristallnacht) because of all the smashed glass.

Kristallnacht (Crystal Night) was ‘sudden’ - in fact someone was killed

and the murderer was supposed to have been a

Jew, but there was no proof at all that the

killer was Jewish. The incident was used as

an excuse to allow a violent, vicious,

destructive outburst against all Jews in the

country.

Not only were businesses targeted but homes

and Synagogues (Jewish places of worship).

Hundreds of people were either killed or

died afterwards or committed suicides.

Thousands of Jews were rounded up and put

into concentration camps.

2.1 Forced emigration

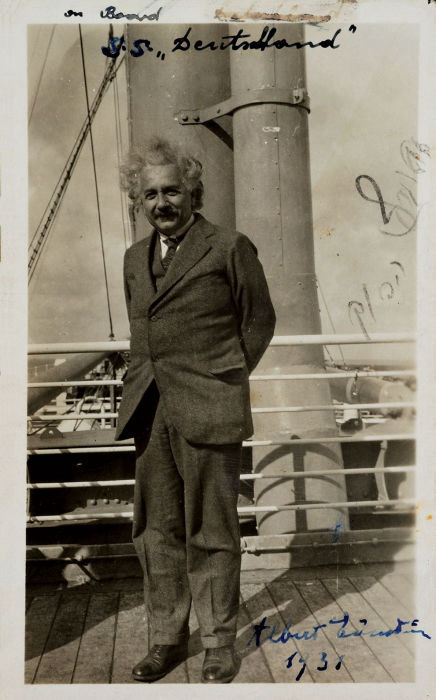

From the start of the Nazi

dictatorship, many Jews with influence,

high reputation or

sufficient wealth could

find the means to leave. The most

popular destinations were

Palestine,

Britain and the

USA, and

among the most renowned émigrés was

Albert Einstein.

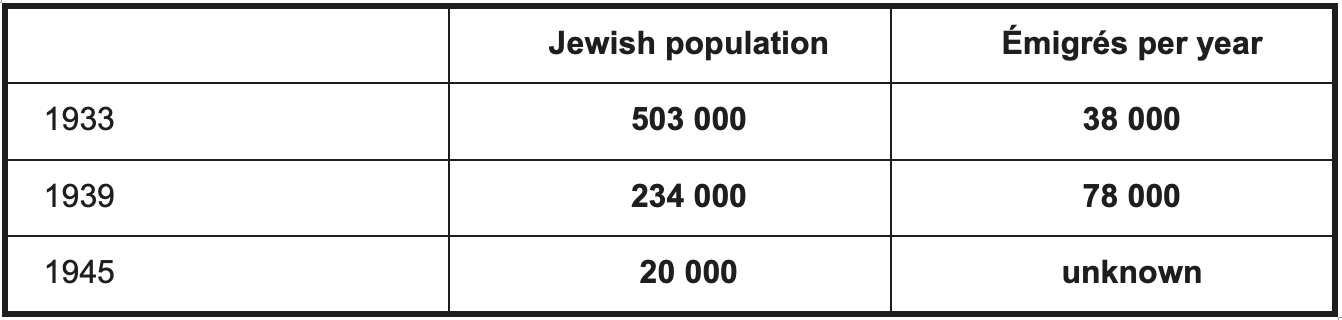

The Jewish community in Germany 1933–45

* The cumulative figure of Jewish émigrés

between 1933 and 1939 was 257,000.